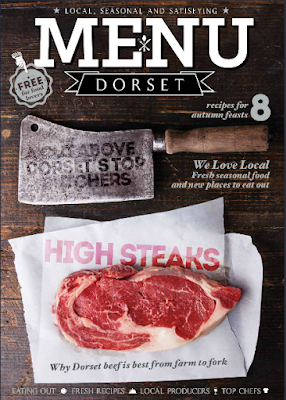

For the cover feature of the October issue of Menu Dorset magazine, I interviewed some of our leading beef farmers and butchers. I gained an interesting insight into everything that leads up to the steak on your plate or the burger on the grill. You can read that article here, beautifully designed and with some outstanding photography. In the following post, I’ve developed some of the thoughts that got me ruminating…

What’s

the beef with beef?

Beef accounts for 12% of UK agriculture, but the industry

is facing some of its hardest challenges yet. A quick stat attack:

- There are just 6,000 butchers

left in the UK, down almost 60% in 25 years.

- In 2011, we were producing

935,000 tonnes of beef and importing 381,000 tonnes from abroad.

Crucially, we’re producing less than we consume.

- By 2007, the number of

abattoirs in England had fallen to just above 200, down from 1,000+ in

1985.

- The size of British beef herds

fell by 27% between 1990 and

2007.

- Between 1996 and 2005, there

was a ban on keeping cattle older than 30 months because of the BSE

crisis.

- More than a thousand dairy

farms have closed in the last 3 years as supermarkets have driven milk

prices lower than the cost of production.

- There are roughly 10 million dairy and beef cattle in the UK, of which 1.8 million are adult dairy. According to Animal Aid, 10 percent of dairy cows are held in ‘zero-grazing’ indoor units.

And some misconceptions:

- The fat content of trimmed

beef is around just 5 percent. As a valuable source of zinc, protein and

vitamins, it’s healthier than you think.

- Land that cattle graze on is

typically not suitable for any other crop.

How

does beef work?

Typically, it takes about 2 to 3 years for UK beef to go

from farm to fork. In the US, 18 months is standard, and keeping cattle any

longer is seen as wasteful and counter-productive. From selecting the right

semen to measuring the exact amount of required feed, industrial beef farming

eliminates the unknown.

Luckily, we’ve largely avoided going down the route of

the Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation in the UK, but as long as consumers

demand cheaper meat, we’re implicitly allowing the major retailers to make the

case.

The

free range alternative

So it’s encouraging to see a number of beef farmers and

producers in Dorset doing the opposite. Drive anywhere in the county and you’ll

come across rolling valleys of pasture, these days with the obligatory yurt or

tepee encampment often as a final flourish. It’s land that cries out for dairy

or beef farming, the quirkier the better.

What’s

in a label?

To be labelled Organic, the farm must be certified by the

Soil Association and the cattle raised free from antibiotics, pesticides, and

fertilisers. This is the kind of beef you’ll get from Cedar Organic Farm on the Isle of Purbeck.

Otherwise, you’ll want to look out for grass-fed or free

range beef, which is raised on pasture rather than grains, or which comes with

the Red Tractor Assurance.

What’s

great in Dorset?

Martin

Bartlett and family have been farming at East Shivinghamtpon for 70+

years. When the dairy herd was sold in 2009, the farm moved onto a suckler beef

herd of around 300 animals. These are Limousin, Hereford and Aberdeen Angus.

“We’re trying to do it in a very traditional way – they

graze in the summer and come in the sheds eating silage in the winter,” says

Martin. “You’re giving that cow as good a life as possible to grow without

stress. That makes the beef better.”

When the time comes to despatch cattle, the shortest

journey to the abattoir is better, since the animals suffer significant stress

en route. “The slaughterhouse is down in Bridport,” says Martin. “It goes from

us to an abattoir and then from a butcher back to us.”

This is a farm that thinks locally and follows sound

practise. “We don’t waste any of our meat. We only send on an animal to

slaughter when we need more meat. We don’t want to fill up the freezers with

things that we already have,” says Martin. “Food is too cheap generally. That

means that farms struggle. If people buy local produce they can help their

local environment and economy. I’m a huge believer in the local tag for food.

Patricia

Barker raises Dorset Longhorn at the

Bride Valley Farm in Abbotsbury. They’re a three-time Taste of the West Gold

winner.

“We’re the only farm that I know of that turn Longhorn

cattle into beef,” she says. “We buy them as weaned calves then we rear them

and send them to the abattoir at 2 ½ to 3 years. We send about one every week.

We have between 150 and 200 of all ages.”

The cattle are grass fed on permanent pasture. “They have

a very natural life, spending most of their time on a nature reserve called the

Valley of Stones. They’re not in small paddocks or strip grazing. They have the

freedom to roam across a big area. Because they’re good grazers they will pull

out the less palatable grasses.”

In order to remain sustainable, the farm insists that the

restaurants and pubs it supplies do more than just cherry-pick the choice cuts.

“Hotels and restaurants tend to want prime cuts from the hind quarter. If I

sell only that what am I going to do with the other two thirds of the animal

from the fore quarter. So every time I take someone on, I have to spell it out

to them that they have got to take some of the rest,” she says.

Often, that will mean educating those who visit the farm

shop on what they can do with different cuts. “Things like short ribs have

become very fashionable recently. It used to be that people didn’t know what to

do with them. People come into the shop and ask us how to cook different cuts

and that’s one way of educating them. You show them where it comes from and how

to cook it.”

RJ

Balson & Son, in Bridport lays claim to being the world’s

oldest butcher, having started out in 1515. Running a business for five

centuries isn’t just a case of finding your niche – it’s about providing

something that’s better than what’s on offer elsewhere.

“Most supermarket meat it goes in the slaughterhouse live

and it comes out the other end in a tray all wrapped up in plastic. Although it

looks nice and bright, people don’t know what they’re missing,” says Richard

Balson.

“The main thing with beef is that local is better. And

it’s how you keep it. It’s the hanging that’s important. You don’t want it too

fresh. You want to hang it for about 3 weeks. As the muscle begins to break

down it goes darker and will be more tender.”

People not only want meat that looks aesthetically

pleasing, they also want to cook it quicker. Another challenge.

“People want a small joint that they can carve quick and

use it up in one go. If you go back 50 years, it was a bigger joint that lasts

all week and you had it roasted on a Sunday, cold on a Monday, minced on a

Tuesday or stewed and that joint lasted a whole week. Now they want something

that they can cook in 20 minutes. Things have changed so much. People don’t

have the time and we’re all out working, so they don’t have 4 hours to prepare

a meal,” says Richard.

Barbara Cossins runs The Langton Arms in Tarrant Monkton. The

family has been rearing cattle for five generations. One of the main advantages

of buying local Dorset beef, she says, is that “the consumer is guaranteed 100% traceability as well

as 100% British beef and not horse meat, for example. Every Red Tractor assured

farm is routinely visited and rigorously tested to ensure that they are

achieving high standards of animal welfare, hygiene and general farm practice.”

Says Barbara: “All of

our animals are born and reared on the farm and therefore lead stress-free

lives. The only time they leave is for the abattoir that is a short 10-mile

drive away. Our system is extensive and so all our cattle spend most of their

time grazing on the pasture rich Dorset downland that is superb for

growing healthy animals. We also utilise our own homegrown feeds rather

than relying on imported feeds, and so we run a completely self-sufficient

system.”

One of the biggest

challenges she identifies is staying competitive: “This often means narrowing

our margins. It is tough to compete with cheap imported beef, the majority of

which has been intensively reared on barley with high stocking rates. It has

also often had hormonal treatment to stimulate rapid growth in the animals, all

of which results in a significantly cheaper production system than

our own.

Looking to the

future, there is much uncertainty for farmers who are soon going to be running

their businesses outside of the EU. But if there is enough support from

the British public then farmers will hopefully be able to succeed in sustaining

the future of British agriculture and carry on providing quality food

with a mindfulness for the local environment and high animal

welfare standards.”

Conclusions

to be drawn

Quite simply, there’s an enormous difference between a

21-day aged steak from a butcher and a bright pink cut from a supermarket, and

the latter is not necessarily cheaper. But it needs people to get back to their

local butcher. That means butchers also need to work harder to stimulate

interest and educate. The Langton Arms, for example, produces its own booklet

explaining how to cook different cuts of meat.

We’ve lost a lot of skills where cooking beef is

concerned. We’ve also lost contact with where our beef comes from, something

that is changing in Dorset. Nowadays you can visit, camp out at, or even lend a

hand on quite a few of our farms. As the saying goes, it’s time to sell the

sizzle not the steak.

No comments:

Post a Comment